I was very saddened to hear today that Bertrand Tavernier passed away. He was one of my favourite cinephile directors and his knowledge, breadth and passion for cinema could not be matched.

I first learned about Tavernier when I stumbled onto his gigantic interview book MY AMERICAN FRIENDS while browsing the shelves at the Toronto Reference Library (because I’m a nerd). The book was so massive that I couldn’t help but pull it off the shelf, and within it, I found a treasure trove of interviews that Tavernier had conducted with filmmakers (both famous and forgotten) over the last few decades. At the time, because I didn’t recognize most of the people he interviewed, so I skipped to the ones that I did: Joe Dante and Quentin Tarantino. Both of the discussions they have with Tavernier are film geekery of the highest order and it’s a shame that the book was only available in French.

Until now!

In honor of Tavernier, and in the hope that will encourage people to go explore his great body of work (which a lot is currently available on the Criterion Channel), I present the first half of the interview that he did with Tarantino – a love fest about the director William Witney, a discussion about finding your own filmmaking masters, and a discussion about what makes an auteur. If there’s enough interest, I’ll dive into PART 2.

Please enjoy.

BERTRAND TAVERNIER: Quentin Tarantino, we’ll no doubt talk about your films, but I wanted to interrogate the links that exist between your work as a director and your vision of cinema, your culture, your influences… In particular, I would like to know how your cinephilia started and evolved.

TARANTINO: Sure! That’s cool.

BT: When you appeared on the global cinema scene, three things hit me: You were a talented filmmaker, you were a passionate cinephile, precise and never obvious, et thirdly, for you, one doesn’t go without the other:

QT: Oh! Thanks, Bertrand. Stop with the compliments!

BT: I believe that cinephilia needs to be a living thing and that loving cinema doesn’t end after the first viewing of a film, that it’s constantly evolving and that there’s nothing defined…

QT: I agree with that. Haven’t you noticed that there could be a school of thought corresponding to a specific kind of cinema and then you see, thirty years later, that’s not the case anymore?

BT: Yes, and that’s without considering what we can learn with time. During my first interview with writer/producer Philip Yordan, he completely took me for a ride. He spoke of the themes of MEN IN WAR (1957), which was written by Ben Maddow, or CID, written by Ben Barzman, who also wrote THe fall of the Roman Empire (1964), under the name of Philip Yordan. Ben Maddow, was, of course, the guy that wrote most of the work that he signed…

QT: It was a nickname?

BT: Yes. And at the same time, he was a fascinating character: He possessed a troupe of screenwriters and he won Oscars for scripts he hadn’t written a line of,..

QT: Absolutely. It’s like “The Other History” of Hollywood.

BT: Speaking o f the other history of Hollywood, let’s talk about one of your director obsessions: William Witney. How did you discover him?

QT: Here’s what brought me to him: If you’re a cinephile, historian of cinema, or just a student, there’s a moment where you go “Have I seen everything that there is to see?” or even: “Are there still a movie that can surprise me?” The answer, as we know, is that there is. But there’s also a time when you think: “I’ve seen all the classics, and I even have an opinion on the ones I haven’t seen.” And there, if you’re a serious person, you tell yourself: “Ah, wait a minute, do I really know the works of this person? Are they really auteur? Just because Andrew Sarris decided to write about them and not the others?” When I was a young cinephile, I remember learning about the different filmmakers. I would get a videotape, a western, with a cover that said Randolph Scott’s name in big letters. Right away, I would tell myself “Is this a Randolph Scott directed by Budd Boetticher or by Andre De Toth?” Later on, when I knew all of the work of Boetticher and that of De Toth, I was able to say: “Maybe it’s a film directed by Roy Huggins?”

BT: Ah yes, his only Scott: HANGMAN’S KNOT (1952) is excellent!

QT: Absolutely, HANGMAN’S KNOT is an excellent film. And so, when you see a film directed by Ray Taylor, you shouldn’t tell yourself: “Andrew Sarris didn’t write about him, it must be shit!” Just because Andrew Sarris didn’t mention him?” I even went further. I told myself: “It’s the opposite. Who are the ones Sarris never wrote about?” So, that’s how I started.

BT: Tell me about it…

QT: I started in the forties and fifties. I was hoping to discover my own masters. I first discovered types that weren’t too far from my goal, but I was really looking for something that would excite me. One day, I saw THE BONNIER PARKER STORY. A film from 1958, which I remembered seeing as a child. I was able to find a 16mm copy for my personal super collection. Just based on the title, not the director. I watched it right away and asked myself: “Who is this director? William Witney? Who the hell is William Witney?” I did some internet research, and unfortunately, the internet is often full of lies. You gotta look IN BOOKS. If you don’t go to the library, your research will come to nothing. I dived into it. Results: This guy was the king of serials; he made twenty movies with Roy Rogers; he finished his career making blaxploitation. He even made a fucking rock’n’roll film with Lesley Gore and the Beach Boys. My God! Right after working with Republic, he joined AIP, which I would have exactly done in his place… This guy was made for me! So, I started to look at his work and I have to tell you it was one of the most amusing things I’ve done in my life as a movie viewer. You know very well, cinephiles are always on the lookout for something, it’s like a hunt. At 19, after seeing my first videotape, I told myself “I’m going to watch all the films of Howard Hawks.” I will watch all the TV programs, I will study films until I know them by heart, the titles, the actors, the credits… The problem is that he made a lot of them. I was even waiting for some of them not to be good, but film after the film, Hawks proved the contrary. He became my master. He’s a relaxed master, a master that I wasn’t the first to discover, but that I discovered by myself, that I appropriated.

BT: Let’s get back to Witney. When we started our film club in France, the Nickel Odeon, at the end of the fifties, we did show DAREDEVIL OF THE RED CIRCLE (1939)

QT: That’s a great film!

BT: Witney had a little reputation. There was a cinema called Le Studio Parnasse where every Tuesday, after the film, there would be a debate between the owner of the cinema, Jean Louis Cheray. He also had a notebook for requests, in which Francois Truffaut had requested multiple times to see G-Men vs the Black Dragon, which dates from 1943…

QT: No?! Seriously?

BT: It was like a legend that circulated. Because Truffaut had wanted to see the film, it contributed to Wintey’s reputation and we wanted to see all teh films that Republic produced. I remember going to the Far-West to see SANTE FE SECRET PASSAGE (1955)

QT: Far-West? Is that the film’s title in French?

BT: No, it’s the name of the cinema…

QT: A cinema called The Far West? Amazing! Did they just show Westerns?

BT: They showed a lot of them, and after that, it became a porno theatre! So, we say SANTA FE PASSAGE and OUTCAST (1954) with John Dereck.

QT: Amazing picture. Do you know PARATROOP COMMAND (1959)? One of the best budget films about the second world war from that time!

BT: Yes. We saw it at a cinema that was the last to have live shows before the film started: There was a whistler! Before the film, he walked on stage and said: “And now, I’m going to be canary…” The name of Witney will always be linked to a man that imitated birds…

QT: It didn’t keep you from remaking that, with WItney, the camera moves were very elegant.

BT: Yes, in his serials, at time the intrigue could be very stupid and the acting could be very broad, but Witney had the best fistfights.

QT: William Witney is the inventor of the American Fistfight as we know it in cinema.

BT: ANd his exteriors were always well filmed. When you compare him to the other serial directors, he was infinitely superior.

QT: Especially compared to guys like Spencer Gordon Bennet… Witney had incredible tracking shots, and he did them for years. Ah! The travelling shot with Roy Rogers walking way on his horse Trigger… And the start of SANTA FE PASSAGE, there’s a camera move…

BT: … on a window? I saw the film 35 years ago and I still remember it! But you’d remember better than me…

QT: We’re in a saloon: John Payne, who’s playing the leader of the convoy, and his partner Slim Picken, enter. They’re drunk, but happy, because they succeeded in duping some Indians and saving their caravan. But something tells us that the saloon, which is filled with cowboys, is hostile towards them. It’s then that the camera does a subtle move to the back of the saloon onto the bodies of the kids from the convoy. In truth, the Indians massacred them. The camera turns back onto our two heroes to watch the cowboy punch and jump them. As the fight extends to the outside, the camera still inside, moves to the window to look through the window. When I discovered this shot, after seeing quite a lot of Witney, I remember saying to myself, yes “Elegant” is the right adjective. That’s what I’ve always used when discussing that shot. What work it must have been to move the camera so fluidly and so discreetly. He had so much class and style in that scene. With all his serials, Witney had made 30 films before reaching Santa Fe Passage.

BT: I met Witney.

QT: Oh! My god, you met him? That Bertrand is very cool. At the time, no one knew him in America.

BT: En 1964, in Hollywood, I visited a stage that was shooting an episode of Bonanza. I spent all day watching him work. And then I met him in Paris. I asked him if he had shot scenes for films where he wasn’t credited and he responded: “Yes, one or two” For example, he’s the that shot the attack in THE WOMAN THEY ALMOST LYNCHED (1953) for Allan Dwan.

QT: That’s the best scene of the movie! And it’s the Dwan that I prefer the best. Of course! Ben Couper is in that and he’s a favourite of Witney.

BT: You’ve never met any actors that worked with him?

QT: I went to go see Martin Landau, who worked with him on an episode of Bonanza. He told me “Witney was a good man. I was playing a boy that had been hung and had a neck scar. When my character was going to be killed, instead of falling, I got back up and Witney told me it was a very good idea, and that I should do it that way.” That was typical of Witney. When I directed an episode of CSI, I cast Andrew Prine in a role and he told me about shooting the series THE WIDE COUNTRY. He only had a small role in one episode, so I was surprised that he remembered it. He told me “Witney was a person that was difficult to forget.” And you, what else did you learn?

BT: That Witney also did the battle of the Alamo in THE LAST COMMAND (1955) for Frank Lloyd

QT: That I knew! Lloyd was sick and Witney shot most of the action scenes of the film. Of course, they’re the best ones. When he worked with John English, English did the dialogue scenes, the suspense scenes, the scenes with the evil Mexicans, ect. And all the exteriors, the grunt work, that was Witney’s job!

BT: Witney told me that Frank Lloyd was one of the most charming directors in the business, a real gentleman. Witney also played a general in THE WILD BLUE YONDER (1955) directed by Dwan. His favourite film was STRANGER AT MY DOOR (1956)

QT: That’s a very well-made film, but not my favourite – there’s a difference, right? In terms of proper value and sentinel value, but if I had to show a single film to prove that Witney was a great director, that’s the one I would show. And thanks to that film, Witney got television offers.

BT: I find it very original, with little action, and room for the characters. I remember one scene “vidorienne” with a horse, at night.

QT: That scene is one of the great scenes in the history of action cinema, one of the most beautiful sequences that one could ever do with a wild horse. It arrives close to the top of my rankings, right behind MONTE WALSH (1970) by William Fraker. At the television, in the sixties, all the shows had their episode with a wild horse. “Here’s the episode where our hero will face off against an undefeatable horse!” Clearly, when people from television saw that scene from STRANGERS AT MY DOOR, they went “This Witney, he’s our guy!” That said, we find in STRANGER AT MY DOOR what we like with Budd Boetticher or Anthony Mann: A hero in an impossible situation. And also, in that film, there’s something that few specialists talk about, a religious dimension. In general, in American cinema, it quickly becomes propaganda and usually results in bad movies. The most interesting Christian films are the ones that don’t shove their message down your throat.

BT: In STRANGER AT MY DOOR, it’s done in a fairly subtle way.

QT: Yeah, it’s the type of film where we can argue for hours about the motivation of the characters. On one side, we have the man of the West, a pastor that’s an idiot for abandoning the wife he’s supposed to protect. In our society, we must protect our wives, but in that time on the frontier, we had to physically protect them, right? The leader of the gang could very well be a rapist, for what she knows of him. So, the idiot priest makes the stupid mistake of putting his wife in danger. We clearly see she wants nothing to do with it, so what is she doing with him? Ah well, in this film, all the points of view are legitimate: everything is very deep, fuck, very deep… There are three or four points of view that are evident which could lead to long debates. Who is right, who is wrong? At first, the conversion of the bad guy isn’t the most interesting thing, even if it’s the film’s principal theme.

Witney is also the one who films animals the best in the history of cinema: Trigger, who was the star in over twenty films. After that, because he had a lot of affection for animals, they weren’t second-class citizens. Take for example the family films where there’s a husband, a wife, a kid and a dog, in a Witney film, the dog could go left and the camera would follow him. For ten solid minutes, the subject of the film is the dog!

BT: The family films with a dog, that was its own genre…

QT: … in which Witney didn’t really participate. Other than the Roy Rogers, where he used Trigger more than normal, he never directed a family film. But in Westerns, he had a compassion for animals that was unique.

BT: What do you think of THE BONNIE PARKER STORY?

QT: That’s my favourite. You remember WILD AT HEART (1990) by David Lynch and the cigarette that burns in a giant close-up? That was already in THE BONNIE PARKER STORY! See, Palme d’Or at Cannes. You remember the dialogue?

BT: Yes: “We will be together until death separates us.” We’re in the marriage, we hear that reply, and right after there’s a cut, and we see a superb murder set-piece!

QT: Exactly! And it gets really interesting when you compare it to Arthur Penn’s film. The two films each tell the “true” story of Bonnie and Clyde. Arthur Penn obscures one of the most famous things they did at the time: They blew the brains out of a cop on his patrol. It’s their most famous story! Even more than their hold-ups, it’s because they pulverized the head of a cop! It made them famous in the thirties. They were completely crazy! And, we get that scene in THE BONNIE PARKER STORY. And that scene is in this film and nowhere else!

BT: And then there’s Dorothy Provine…

QT: She’s so totally excellent! And for me, the dialogue in THE BONNIE PARKER STORY joins those of OUT OF THE PAST (1947), HIS GIRL FRIDAY (1940), as the best in the history of cinema. The one who wrote the film is also the producer, Stanley Shpetner. He also wrote and produced PARATROOP COMMAND in which the dialogue, there as well, is brilliant.

BT: I remember in PARATROOP COMMAND, the violence is treated abruptly, without manipulation. There’s a sequence where we see bodies burn, literally in flames.

QT: Yep. And that film is impressive in its melodramatic character. But when it gets real, it’s even more exciting. Not to say I don’t love melodrama, but when it disappears in a flash, the film takes a crazy modern turn. In PARATROOP COMMAND, it’s the same. We follow the destiny of the soldiers, and in a flash, in an unconventional plot, far from any heroic sentiment, they’re killed one after the other. Boom! Boom! It’s very realistic: one type dies, and then another type, and then a third! We tell ourselves “Shit, all the characters we created a connection with are dying!” Without warning, without ceremony, without music. They all fall like flies and that’s it!

BT: What you’re saying reminds me of a big war scene, that is totally underrated and never mentioned in any books: The flash back in MONKEY ON MY BACK (1957) of De Toth.

QT: Oh yea! I know that one! A scene without dialogue, without music, under the rain, in the mud…

BT: A violent scene, cold , pointed… A butcher shop, the war in his reality, with people that die.

QT: That’s some great Andre De Toth! And some great Cameron Mitchell! Him, I love! That’s a great example and a magnificent film.

BT: There again, why don’t critics mention that in ten-twelve minutes – and that’s long, ten minutes – we have one of the greatest war scenes ever realized?

QT: To my eyes, that’s the beauty of these great filmmakers. They worked in front of a press that ignored them. For critics, their work barely existed! So they made the movies for themselves, for the art, for their friends as well, who recognized their work. It’s true everywhere: your work is often ignored by the press of your own country. At the very least, let’s say that it is taken for granted. The people who quibble are always the critics back home.

BT: Why do some directors spend so much energy and imagination? Sometimes, they weren’t even linked to a studio. I remember a film from 1936, realized by Robert Florey called The Preview Murder Mystery …

QT: Haven’t seen it.

BT: Or to THE MONSTER AND THE GIRL (1942), a film noir by Stuart Heisler. Where did they put so much passion into it? It was not with that that they were going to be recognized by the studios, nor by the stars.

QT: Let me return the question to you. How do you go to so much trouble and see your work go into the atmosphere? As a filmmaker, would you accept it? I wouldn’t!

BT: But they did it anyway.

QT: Yep. They did it anyway. We have to say their world was different: They didn’t hope for critical success, they may not have even cared. They just wanted to do their best, and be as creative as possible. Maybe they did it just so they could get to the end of their day of work.

BT: That last explanation is the most plausible.

QT: There weren’t any great critics either…

BT: Still, there were people like James Agnee who highlighted the value of Val Lewton, or like Manny Farber who rated LITTLE BIG HORN (1951) by Charles Marquis Warren at the head of his best films list.

QT: Charles Marquis Warren, there’s someone that made great films. I have a 16mm copy of HELLGATE (1952)

BT: I’ve never seen that one. How is it?

QT: Very good!

BT: I’m often surprised at the way ‘Auteur’ is used by Americans in regards to its original definition. According to Chabrol, we would recognize an auteur even before his name appears on screen, just based on his style, his themes and his sensibility. But he also said, and we’ve forgotten this: “All the works of an artist can not be perfect.” So, you can be an auteur and make bad films.

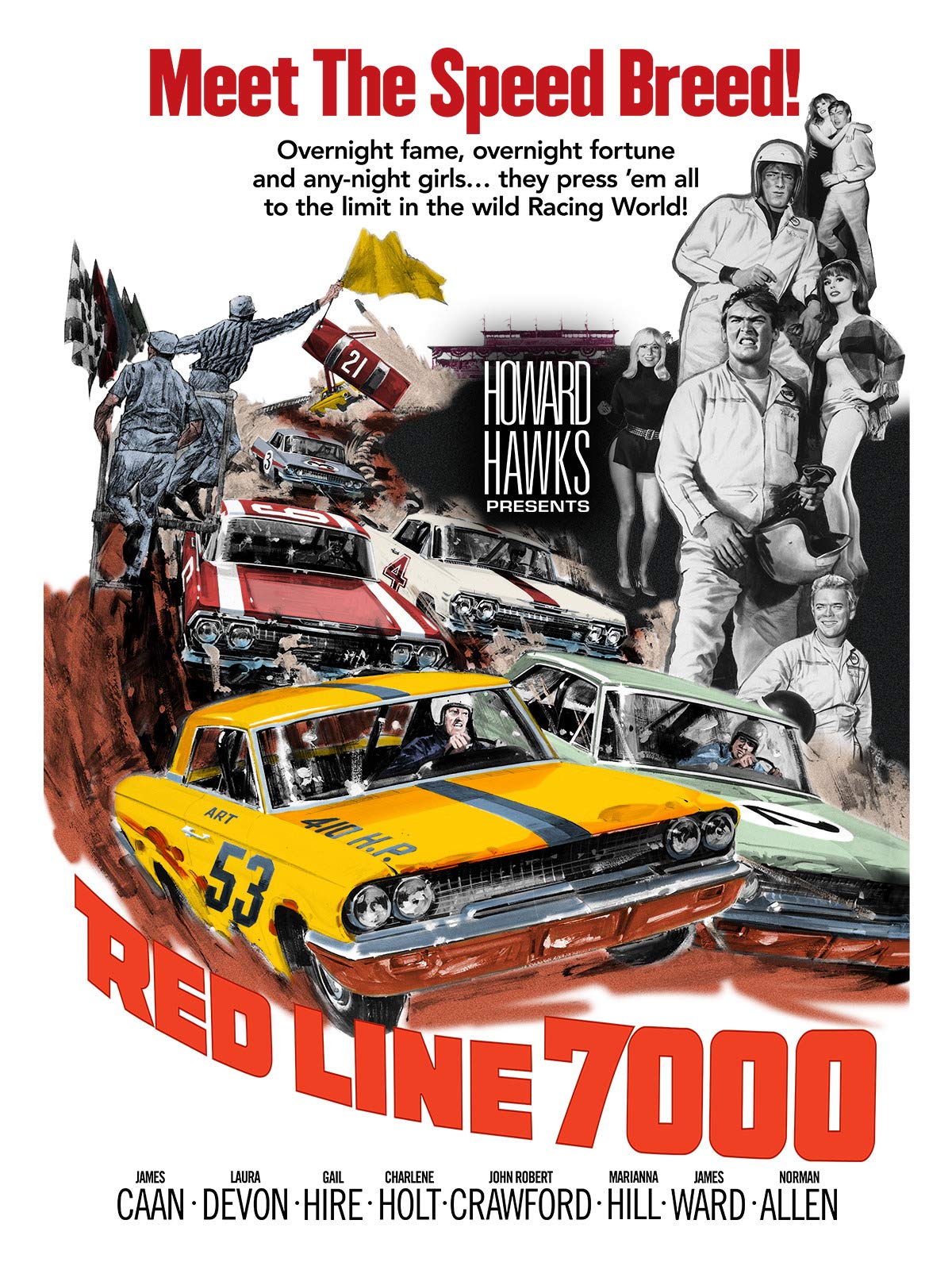

QT: Obviously. Let’s take Hawk’s REDLINE 7000, it’s considered by American critics as one of the worst films in Hawk’s career…

BT: Not in France!

QT: Really? Here, it wasn’t loved, yet it was, at the precise moment of its release, the most modern in the genre of “race car movies.” Kind of like when Jim Sheridan recruited 50 cents, the rapper, for GET RICH OR DIE TRYING (2005). It is perfectly in tune with the times. When Hawks recruited James Caan for RED LINE 7000, he was making a Presley picture, and didn’t cast Elvis, but James Caan! And even if it resembles an “Elvis Presley movie”, it’s a Hawks movie.

BT: Yes, RED LINE 7000 is one of his most Hawksien films and is still one of his worst! We can even say it’s an auteur film, but everything is terrible: the script, the acting, ect. But it’s a personal film.

QT: I totally agree, except for me, I don’t find it mediocre. I really like it, like MAN’S FAVORITE SPORT (1964), even though it’s an avatar of BRINGING IT UP BABY (1938)

BT: MAN’S FAVORITE SPORT? It’s very well written and acted, which is not the case of RED LINE 7000.

QT: I know! Red Line is charming in its own way. RIO LOBO (1970) isn’t in the same class as RIO BRAVO (1959) and EL DORADO (1966), but it’s not without charm. Hawks wasn’t in fashion in the seventies. But we can’t help but find him charming. Like in Rio Lobo, when Jack elema points his nose, that’s some Hawks stuff! And when John Wayne beats up Victor French, that’s pure Hawks! The film is kinda “bullshit”, up until the moment when Jack Elam shows up… For me, it’s clear: between the characters of Arthur Hunnicutt, Walter Brennan and him, he’s the best Jack out of all of them! Even if Walter Brennan is amazing in RIO BRAVO, Jack Elam is just as a good in RIO LOBO…

Thank you!

Thanks for putting this up, Justin. Am going through a deep dive of Tavernier’s collected work with some reading up on the man, so this is a nice “extra” for the cinephile in me. Keep up the great work on Important Cinema Club!