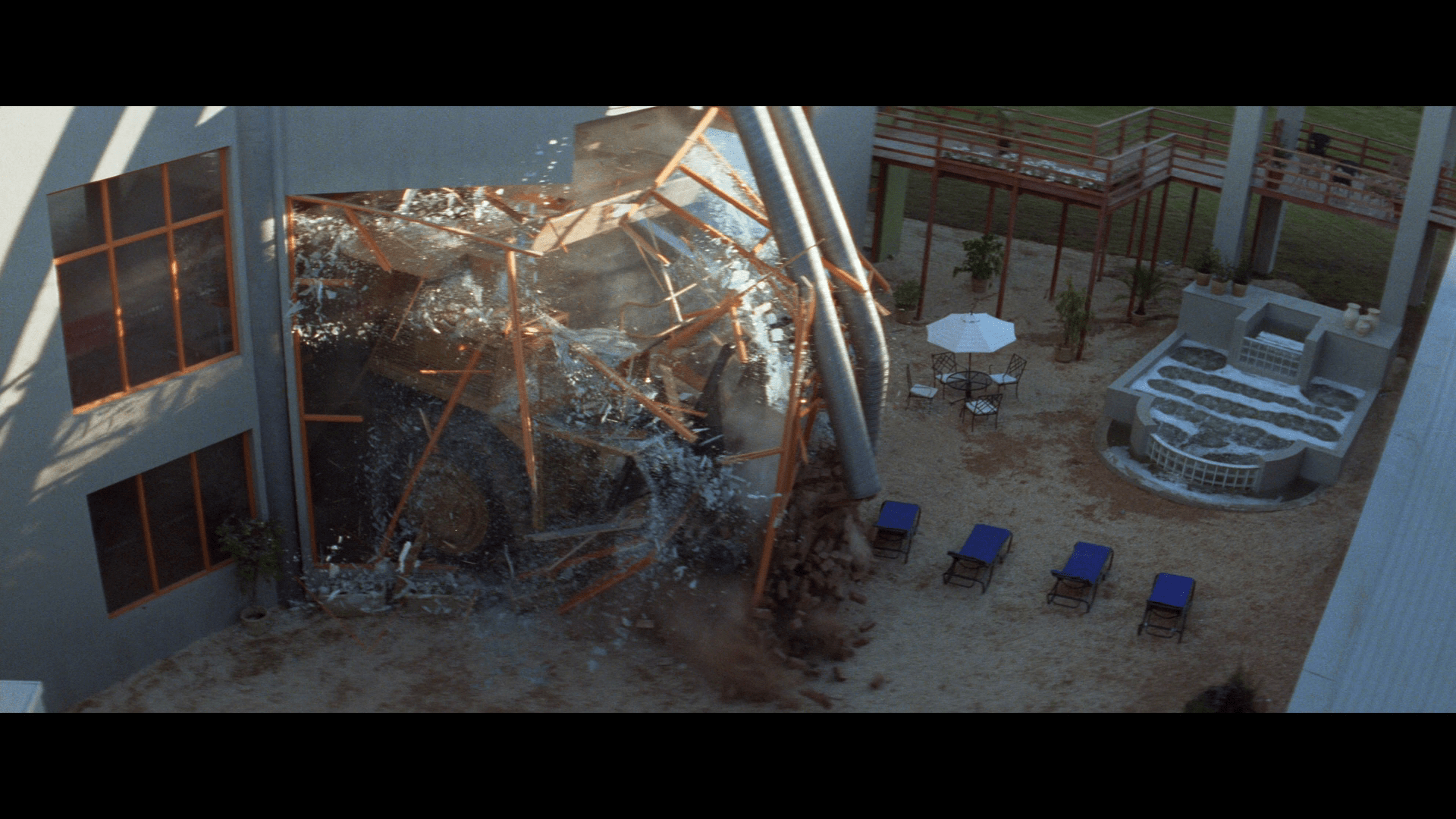

MR. NICE doesn’t feature a climactic fight. Jackie doesn’t take on the blond-haired guy that’s been chasing him throughout the picture, nor does he have an epic matchup with the big bad played by Richard Norton, the excellent Australian martial artist that Jackie had previously fought in CITY HUNTER. Instead, Jackie drives a monstrously large construction vehicle through a mansion, causing the edifice to explode, which is documented in glacial slow motion from multiples angles in a sequence that echoes the finale of Antonioni’s ZABRISKIE POINT. And while ZABRISKIE was closing the book on 60s idealism, the vehicular mayhem of MR. NICE GUY is the last gasp of Jackie’s work as a boundary-pushing martial arts genius.

MR. NICE GUY (1997) landed smack dab in between Jackie’s biggest English market hits, RUMBLE IN THE BRONX (1995) and RUSH HOUR (1998), and by consequence, it’s often dismissed as a mere time-filler before Jackie’s star rose in North America’s public consciousness. It’s the film people high off RUMBLE randomly grab when searching for a fresh Jackie fix alongside the likes of PROJECT S and ISLAND OF FIRE. Speaking of its generic reputation, the North American poster of MR. NICE GUY is the much-reproduced image of Jackie in a black t-shirt, face scrunched up as he throws a punch, a photo that would be slapped on hundreds of bargain bin DVDs of old-school Jackie titles like SHAOLIN WOODEN MEN to trick unsuspecting consumers.

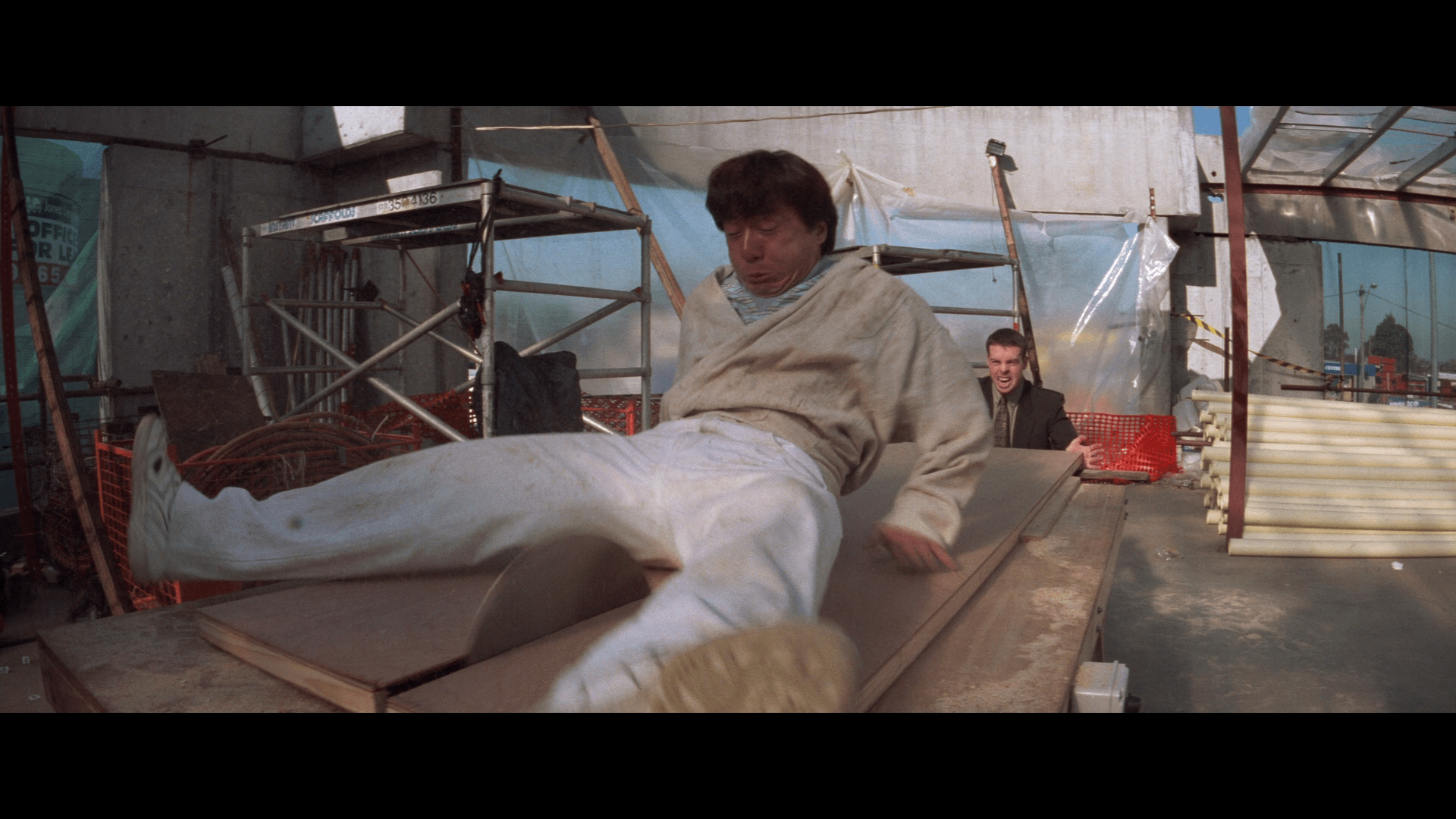

Yet, re-watching MR. NICE GUY on the beautiful restored Warner Archive Blu-ray, I found the film to be Jackie at his most inventive, fast-paced and charming. As a performer, he may have already been past his prime age-wise, but you’d never know it because all the elements that define him as a prop-based stunt acrobat are fully in place. It’s impossible not to marvel at an opening series of set-pieces in which Jackie accidentally gets involved in a multi-person fight, jumps over a high wall, crushes a baddie with the top of a truck, and then crashes a multi-biker wedding that somehow results in him being lifted off the ground by a dinosaur balloon – and that’s all before the fifteen-minute mark!

While RUMBLE had been a huge hit in Hong Kong and had been followed quickly by two other Jackie vehicles, the disappointing race car-centric THUNDERBOLT (1995) and the half-hearted POLICE STORY FIRST STRIKE (1996), it was the American success of RUMBLE IN THE BRONX that caused Jackie to retool the next Police Story film into. NICE GUY: It turned into an English Language production that was shot in Australia, filmed in with on-set sound, and packed prop-based fights. There was even another gang of comically goofy punks! But most importantly, Jackie hired one of the best directors to ever work in the action genre to helm the picture: Sammo Hung.

Sammo had been Jackie’s older brother at the Peking Opera school, and he had carved out a very successful career as an actor/director/choreographer, which often intersected with Jackie’s own: Sammo brought Jackie on as a stuntman in Bruce Lee’s ENTER THE DRAGON (1973), they both acted in John Woo’s HAND OF DEATH (1976), and Jackie co-starred and cameoed in many Sammo productions like the MY LUCKY STARS series of films.

Sammo had always understood Jackie’s style, but he crucially imposed his own creative imperatives when they collaborated. Sammo had developed an action vocabulary throughout his career that had reached its peak power in MR. NICE GUY – swift camera work, fast edits, and big hits. In comparison, Jackie preferred to let things play in wides (Chaplin-esque), which was the antithesis of Sammo’s aesthetics of impact. MR. NICE GUY ended up being two distinct personalities mixing together into a fascinating final form: Jackie gets to do all his schtick, but within Sammo’s stylistic construct that moves with him, instead of backing off to give him space – which is fascinating to watch when you consider nothing of the sort would happen again. From MR. NICE GUY onward, everyone got out of Jackie’s way, and his work suffered immensely for it.

If one highlights Jackie’s most successful films they’re the ones where he rubbed shoulders with amazing creative partners: Lau Kar-Leung on DRUNKEN MASTER 2 (before Jackie fired him), Yuen Woo-ping on SNAKE IN THE EAGLE’S SHADOW (1978) and DRUNKEN MASTER (who Jackie didn’t collaborate with again until THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM in 2007), and most importantly of all, Sammo Hung on way too many projects to list. Take, for example, their roles in PROJECT A (1983): An action classic, filled with jaw-dropping stunts and painful as hell action. PROJECT A: PART 2 (1987) also features some all-timer scenes, but suffers from preposterous bloat that defines all of Jackie’s solo efforts. PROJECT A was directed by Jackie Chan and an (uncredited) Sammo Hung. Project A: PART 2 was Jackie all on his own.

In other words, Jackie needs to be challenged by creative collaborators.

This may sound like blasphemy in light of Jackie’s titanic masterpiece POLICE STORY (1985), a solo endeavour where Chan took the reigns as director, star and choreographer, but one has to remember that POLICE STORY was Jackie’s response to the soul-crushing experience of starring in James Glickenhaus THE PROTECTOR (1985) – where Jackie butted heads endlessly with Glickenhaus on the mechanics of shooting action. Jackie’s POLICE STORY is such a classic because you can feel Jackie pushing himself to show those smug Hollywood no nothings how it’s done. His creative challenge on that project was Hollywood itself!

If one looks at Jackie’s solo efforts as the creative lead, one can witness a brilliant mind that can’t focus. Oftentimes, if there’s no one is there to challenge Jackie’s wild creative impulses, by offering their own stylistic concepts, Jackie gets lost in his own flights of fancy. For example, the epic MIRACLES (1989) features an amazing fight in a rope factory, but the rest of the running time is a big technical demo for techno-cranes with nowhere to go. Jackie’s solo directorial efforts like DRAGON LORD, POLICE STORY 2, WHO AM I? And OPERATION CONDOR may feature some of the best scenes of Jackie’s career (and I own them all on Blu-ray!) but their final form are the tatters of wildly out-of-control productions where Jackie got to play until the chequebook was snapped shut

When I say “MR. NICE GUY was the last great Jackie Chan film!” I mean it’s the last time that Jackie was pushed to his creative limits. Only Sammo, a man who had known Jackie since childhood, could force Jackie to raise his game – and by consequence – Sammo was banished from Jackie’s life for almost a decade. The success of RUSH HOUR made Jackie a North American, star but resulted in films that were a step down from everything that had come before. Jackie in Hollywood wasn’t challenged, he was straight-jacketed, and when he ended back up in Hong Kong all he wanted was complete freedom – which had never worked for him in the past (or for most artists for that matter – just look at the shambolic messes directors let loose on streaming platforms make!). I don’t believe anyone should dismiss everything that followed, because there’s a lot of fun to be had in pictures like NEW POLICE STORY (2004) or the fluffy SHANGHAI KNIGHTS (2004), but from MR. NICE GUY onward everyone is working for Jackie. You can tell he’s calling the shots, and without creative conflict, brilliance is stifled. Watching MR. NICE GUY made me realize that it was a point of no return. It was the stand-out moment where Jackie was at his full power and backed by a team that forced him to push himself to his limit, but following that, he never let it happen again, and cinema history suffered for it.